Funding cuts threaten career development programs for aging fishing industry

A WA Sea Grant program to address the gap is training young people but its future is unclear.

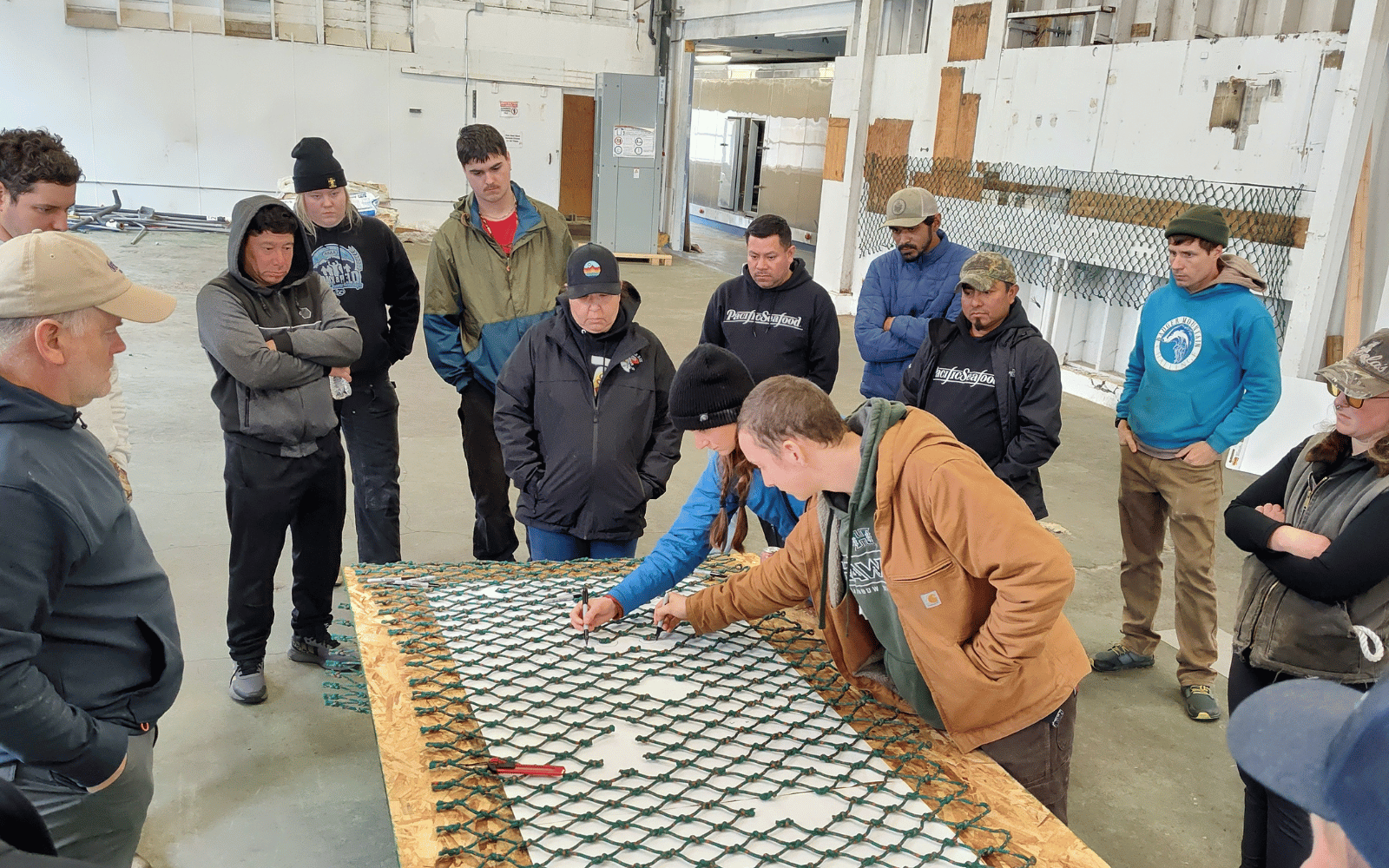

In March, Washington Sea Grant hosted a two-day training for commercial fishing industry newcomers that drew 20 young people to the shores of South Bend, Washington, for an introduction to life at sea.

The course, Skills and Drills, is one installment in a series of federally funded programs designed to revitalize the Pacific Northwest’s maritime sector. Commercial fishing and aquaculture contribute approximately 90,000 jobs to Washington’s economy each year, but there are fewer young people to fill them now than there once were.

“Washington state’s fishing industry has experienced what we sometimes call ‘the graying of the fleet,’” said Melissa Poe, a social scientist at Washington Sea Grant who helped organize the course. Gaps in the workforce create vulnerabilities in the local maritime industry, she noted.

Workforce development programs akin to Skills and Drills bring in fresh blood and give seasoned experts a chance to share generational knowledge. However, many of these programs are now at stake with the threat of funding cuts looming large.

Tensions soared after the Maine Sea Grant lost its funding earlier this year.

“It was concerning for all Sea Grant programs in each state,” Poe said.

Maine's funding was restored, but many Sea Grant programs, including Washington’s, have not received funds promised for 2025 and are not funded in the President Trump’s budget for 2026.

Sea Grant was established by Congress in 1966, and Washington Sea Grant was one of the first four regional programs, designated in 1971.

“We leverage a lot of benefits for every federal dollar spent,” Poe said.

A dearth of deckhands

In 2021, Washington Sea Grant affiliates conducted a needs assessment that identified factors limiting industry growth. This inspired Skills and Drills and the Tides Out program, which offers leadership training to managers in aquaculture.

Last October, Washington Sea Grant was awarded just under $400,000 from NOAA to hold the Skills and Drills course and an associated conference. The funding comes from the Young Fishermen’s Development Act, which Congress passed in 2021 to “preserve United States fishing heritage” via training programs for young fishermen.

During the commercial fishing boom in the 1970s and 1980s, industry barriers to entry were lower than they are today.

“You could get into it for pretty low cost,” said Robert Maw, a lifelong fisherman and Washington Sea Grant fisheries specialist.

Vessels and fishing permits were easier to come by. Fisheries management guidelines limit the number of permits issued to prevent overfishing, which decimated some fish populations in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Navigating the regulations requires “a lot of know-how,” which might deter some newcomers, said Poe.

“A lot of the old guard really got started salmon fishing,” she said, adding that’s not a viable starting point for most people anymore due to salmon collapse and seasonal variability.

Making waves

Skills and Drills kicked off on March 27, at what Maw called “ground zero.”

The course was designed for anyone with an interest in commercial fishing, regardless of their experience level. It covered welding, fiberglass repair, net mending, knot tying, navigation, safe fish handling, and more.

Attendance was capped at 22 participants to balance the student-to-teacher ratio, and South Bend was chosen for its proximity to fishing communities in Southwestern Washington. On day one, triage welding–a means of repairing broken equipment without returning to shore–was a smash hit.

“It was exciting to see,” Maw said.

Even after dinner, people came back for more, reporting that opportunities to practice with the equipment are few and far between. Knowing how to do this kind of quick fix saves time and money on board, he added. Returning to shore comes at a high opportunity cost when you are fishing.

The Port of Willapa Harbor provided three ships for the course, giving participants a chance to explore multiple vessels, including the Ghost Rider.

“We made some holes in it and called it the Holy Ghost Rider,” Maw said. “Their job was to patch it up.”

Participants practiced donning a safety suit, learned where not to stand, how to radio their coordinates, make a mayday call, navigate in the dark, and assist in the engine room.

“It was a lot of fun,” he said, “a great success.”

Charting a course

As for Tides Out, the second annual manager training took place this February and focused on soft skills, like conflict resolution and mentorship, to improve employee retention. The curriculum is available in English and Spanish, and in its first two years, the program supported 39 managers.

Organizers estimate the program’s economic impact to be $10 million, based on the number of people reporting to each manager and their average salary.

Kyle Deerkop, senior farm manager for Clackamas, Oregon-based Pacific Shellfish, attended both the Tides Out and Skills and Drills courses with members of his team.

“We had people in these classes in little old South Bend coming all the way from as far north as Alaska and as far south as California,” Deerkop said. “The West Coast really needs this training and this investment in these industries.”

Other regional training programs are also yielding similar results. Gig Harbor Crew School reported that six out of seven of last year’s participants landed commercial fishing jobs in Alaska.

The Washington Young Fishermen and Crew Conference, also part of the Skills Ahoy program, is scheduled Dec. 4-8 in Westport. The first two days will cover drills and first aid training, and day three will offer on-the-water training.

The conference will cover fisheries management, direct marketing your catch, navigating seasonal work, and running a business. Washington Sea Grant has received funding for the conference, but the fate of future programming is uncertain. “We can’t read the tea leaves,” Poe said.

“We hope that Congress will continue funding our programming,” she added. “We work to support good jobs and healthy ecosystems.”