Sail cargo in the PNW: Why it’s still an upwind battle

Looked to as a sustainable shipping alternative, wind-powered freight has yet to take off in the Pacific Northwest

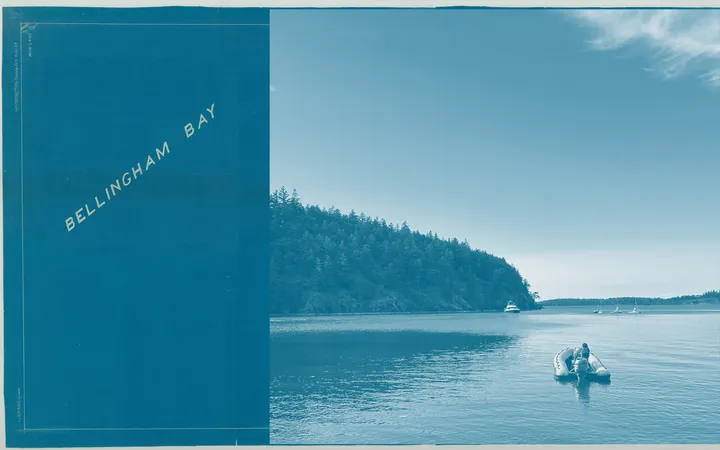

The Pacific Northwest is a coastal region known for its strong commitment to environmentalism. In cities like Seattle, Vancouver, and Portland, this ethos is reflected in a consumer base that seeks out fair trade and sustainably shipped and made products.

Yet one of the most environmentally aligned marine niches to serve this demand—wind-powered sail cargo vessels—remains largely absent from the region’s harbors.

The term “sail cargo” is still relatively obscure in most maritime circles. It refers to a small but growing fleet of vessels (some restored classics, others modern designs) that rely solely on wind to move goods across the water.

This sail-borne resurgence offers a cleaner alternative to conventional shipping. According to the European nonprofit Transport & Environment, international shipping accounts for about 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions, a figure which is projected to rise to 10% by 2050.

The sail cargo industry has gained traction across the Atlantic and in parts of Northern Europe, where vessels—many of which are part of the Fair Winds Collective, a network of organizations promoting wind-powered transport—ride the trade winds east from the Caribbean, Central America, and South America.

Here on the West Coast, few sail cargo ventures have found lasting success, and it’s not for lack of trying.

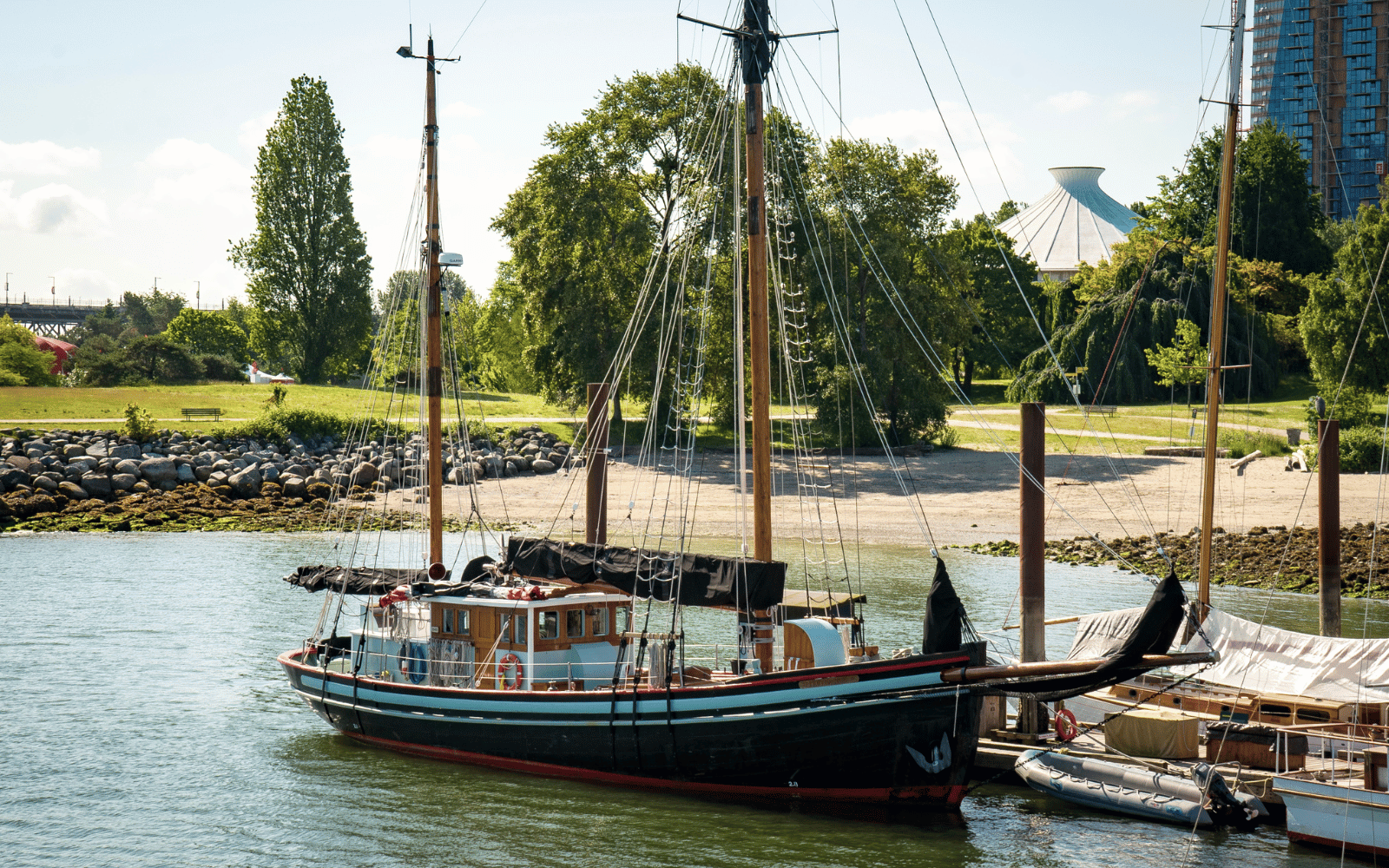

“There’s definitely a barrier to entry,” said Simon Fawkes, the owner and captain of Providence, Canada's oldest operational commercial passenger vessel.

Providence, a vessel over a hundred years old, is one of the few sail cargo ships currently transporting goods in the Pacific Northwest.

Running vessels of this kind is not cheap. Many sail cargo ships are refurbished tall ships, which may offer a lower initial purchase price but require significant investment in upkeep and care. Operating costs, labor, and slim profit margins all present additional challenges for small sail cargo companies.

For Fawkes, sail cargo voyages alone don’t generate enough income to sustain the business without a multi-use model. He supplements these trips with private bookings, day sails, and tourism-based excursions.

“Sail cargo was the original idea, but tourism has become the driver, the necessity to keep it going,” he said.

Keep Future Tides cruising by becoming a Crew Member today!

Your support drives stories like this one and buoys a community-centered publication.

Instead, the company offers a hybrid experience through Providence’s “market voyages,” where paying passengers take part in the sail cargo process—transporting roasted coffee, cider, and other durable goods from the Gulf Islands back to Vancouver markets.

During these trips, passengers—who pay an adult fare of 685 CAD—spend two nights and three days sailing and crewing throughout the Canadian island chain. Along the way, they visit the farms, roasteries, and breweries that produce the goods they help transport back to Vancouver.

Most sail cargo ventures have found success transporting durable luxury goods such as rum, green coffee, cacao, spirits, and olive oil—items for which individual, climate-conscious consumers are more likely to pay a premium due to the product’s story and sustainable journey.

“Things like lumber, for example—no one’s going to pay extra for their two-by-four just because it’s sustainably shipped,” Simon explained. This, in turn, limits the types of goods that can be transported via sail cargo and often demands a complex web of relationships between small-scale producers, shippers, and sellers to ensure the right products reach the right markets at the right time.

Managing these connections requires significant oversight and coordination.

“What people in the PNW might want to understand: while community-based sail transport sounds romantic and easy, it’s not. It really needs to be run like a business,” said Kathy Pelish, managing partner and co-founder of Salish Sea Co-Op.

The Salish Sea Cooperative was a sail cargo venture active from 2009 to 2015, transporting CSAs from Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula to Ballard, Seattle. A network of volunteer vessels formed the backbone of the cooperative, eventually establishing a bilateral trade route between the peninsula and Ballard—entirely free of emissions.

To uphold their zero-emission commitment, the Cooperative even used electric vehicles to move goods from the boat to their next selling destination.

While demand was never an issue for the co-operative, financial sustainability was.

“I closed the co-op due to no profits,” Pelish said.

To close funding gaps or simply break even, many vessels rely on volunteers or charter members to transport goods.

“If I could afford it, I would just do market ship voyages,” Fawkes said.

Beyond the logistical and economic challenges facing the sail cargo industry, there are regional factors—specific to American and Pacific Northwest audiences—that make wind-powered freight more difficult to implement than in the Atlantic.

Timing, for one, plays a critical role in the delivery of sail cargo goods. Every sailor knows that weather can alter an arrival date. Vessels in the Atlantic benefit from the steady rhythm of trade winds, offering enough predictability to build flexible delivery windows into their voyages.

“In these coastal waters, we have wind. But it’s coming from different directions all the time,” Fawkes said.

For Providence, crossing the Strait of Georgia between Vancouver and the Gulf Islands can be challenging in both light and heavy wind. The interplay of tides, gusts, and swell shapes every voyage, and while sail cargo is inherently weather-dependent, the stakes shift when passengers are involved.

“If you're just doing cargo, the cargo doesn't care if it's rough or not,” Fawkes said.

Without guests on board, he can make the crossing with fewer constraints. But when paying passengers are part of the journey, timing and comfort become harder to balance.

“There are lots of times we go out there and we're like, okay, it’s blowing 25 knots northwesterly. And we got to go across today, and I’ve got a bunch of people on board who haven’t sailed before. And you know, that’s not going to be fun for them.”

That tension, between meeting delivery goals and ensuring passenger comfort, can make it difficult to stick to strict timelines, and establish secure shipping routes.

Pelish, whose co-op operated from May through October, took a more conservative approach with her fleet of volunteer vessels.

“We didn’t sail out if NOAA forecast more than 25 knots,” she said. “We had no accidents beyond a ripped sail.”

Audience support is an essential part of Future Tides.

Your questions, feedback, and financial support fuels local news coverage that exists to serve you.

While shipping by conventional cargo carriers remains the most economically viable option, that hasn’t stopped new ventures from trying to take root in Washington State.

Currently, Glory of the Seas, a traditional tall ship moored in the San Juans, is seeking $200,000 for a refit that would allow the historic schooner to operate as a hybrid cargo vessel, transporting goods along the Salish Sea. The project also envisions the ship serving as a platform for research, education, and cultural exchange in the region.

North of the border, Transport Canada has awarded a $1 million contract to Canadian Electric Vehicles (CanEV)—the country’s longest-running EV conversion firm—to demonstrate hybrid sail-electric propulsion systems. One of the main recipients is Providence, which will receive a state-of-the-art electric engine next winter. The upgrade is expected to eliminate all fuel costs and serve as a key milestone in Canada’s push for zero-emission marine transport.

The Jones Act presents another logistical hurdle to replicating the kind of international sail cargo routes seen across the Atlantic.

Formally known as the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, this law requires that all goods transported between U.S. ports be carried on vessels that are U.S.-built, U.S.-owned, and U.S.-crewed—creating barriers for foreign or nontraditional ships and often driving up domestic shipping costs.

In contrast, sail cargo vessels operating within the European Union routinely offload goods in multiple countries and ports, enabling not only a more dynamic exchange of products but also the potential for more profitable routes.

Despite the hurdles, the vision behind sail cargo endures: a slower, cleaner, more intentional way of moving goods through the world. In the Pacific Northwest, that vision has yet to prove economically self-sustaining on its own—but it hasn’t disappeared.

Fawkes’ Providence and Glory of the Seas stand as reminders of a future in which tall ships might once again become part of the region’s working waterfronts.

“I think there is potential here,” Fawkes said with confidence.

Whether that potential can evolve into a sustainable shipping model is an open question, but momentum, however modest, is building.